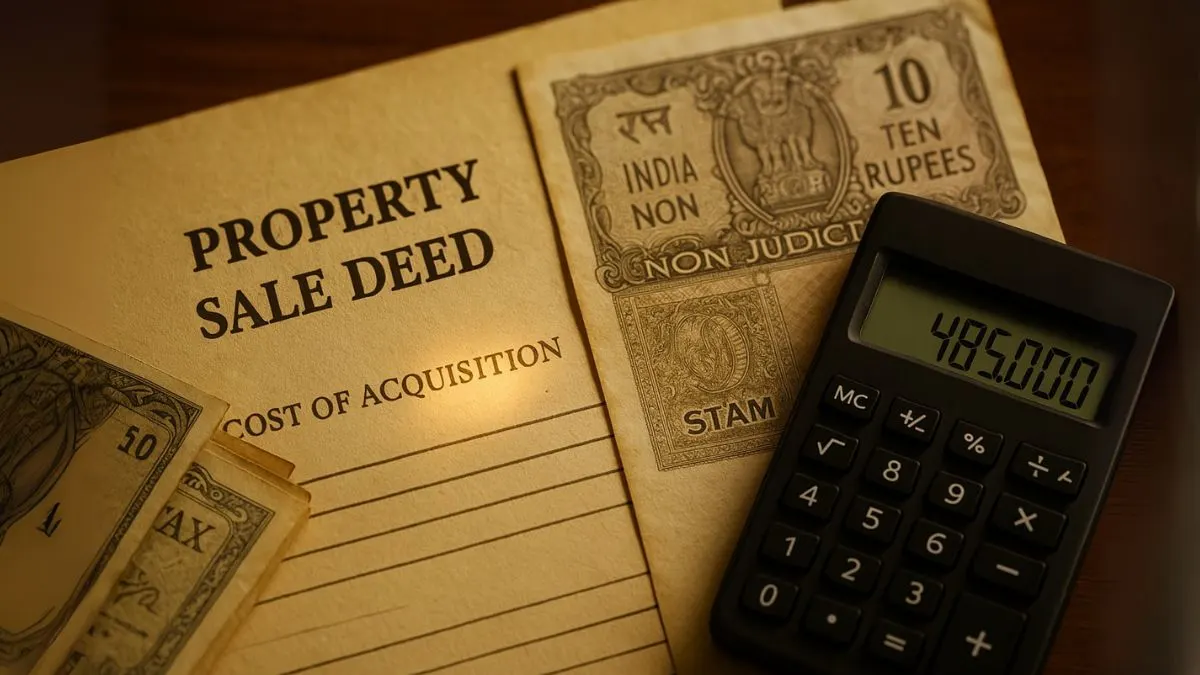

When you sell a capital asset—like property, shares, or gold—you pay tax on the profit. But what if you didn’t actually “buy” that asset yourself? Maybe you inherited it, received it as a gift, or got it through a will. How do you calculate your capital gains then?

That’s where Section 49(1) of the Income Tax Act comes into play. It outlines the calculation of capital gains arising from the transfer of capital assets when the asset was not purchased by you directly but acquired through specific modes like inheritance, gift, partition of a Hindu Undivided Family (HUF), or certain business restructurings. In these cases, the Cost of Previous Owner is deemed as Cost of Acquisition for you.

This provision ensures fairness—so you are taxed only on the gains that happened after you owned the asset, not on appreciation that occurred before you got it.

What Section 49(1) Really Says

Under Section 49(1), when a capital asset is acquired in any of the below ways, the Cost with reference to certain modes of acquisition is taken as the Cost of Acquisition to the previous owner:

- Inheritance (under a will or by succession)

- Gift without any consideration

- Partition of a Hindu Undivided Family (HUF)

- Distribution of assets during company liquidation

- Amalgamation or demerger of companies

- Business reorganization of co-operative societies

For example, if your father bought a plot of land for ₹5 lakh in 2000, and you inherit it in 2023, you will take ₹5 lakh as your cost of acquisition—not the market value in 2023."

Why the Law Works This Way

The rule prevents you from being taxed on gains you never made. If you had to pay tax on the total value increase since the original purchase, it would be unfair—you didn’t earn that entire profit, only the appreciation after you got the asset.

By allowing you to adopt the Cost of Acquisition to the previous owner, the law ensures you’re only taxed for your period of holding, while also allowing you to consider the indexation benefit from the year the previous owner first acquired the asset.

Modes of Acquisition Covered Under Section 49(1)

Here’s a breakdown of the common cases where Section 49(1) applies:

- Inheritance or Succession

Assets passed down through a will, succession, or legal heirship. - Gifts

Assets received as a gift, provided they are not taxed under other provisions like Section 56(2)(x). - HUF Partition

When an asset is allotted to a member during the partition of a Hindu Undivided Family. - Company Liquidation or Restructuring

Distribution of assets in liquidation or under schemes of amalgamation/demerger." - Business Reorganization

Applies to reorganization of business entities like firms, LLPs, and co-operatives.

Also Read: Filed ITR Will Become Invalid Unless Verified Within 30 Days

Capital Gains Calculation Under Section 49(1)

When you sell such an asset, the capital gain is calculated as:

Sale Price – Indexed Cost of Acquisition (as per previous owner) – Cost of Improvement – Transfer Expenses

Example:

- Previous owner bought the asset in 2005 for ₹10 lakh.

- You inherited it in 2020.

- You sell it in 2024 for ₹50 lakh.

Your Cost of Acquisition = ₹10 lakh (indexed from 2005), not 2020.

Indexation Benefit – A Big Advantage

A key benefit of Section 49(1) is that you can take the holding period and indexation from the date the previous owner acquired the asset, not when you got it.

This can significantly reduce your tax liability because the indexed cost will be much higher.

Special Case – Cost with Reference to Certain Modes of Acquisition

In some cases, the Cost of Acquisition to the previous owner may be adjusted for improvements made to the asset. For example:

- If the previous owner renovated a house before gifting it to you, those costs are also added to your acquisition cost.

Tax Rate Applicable

While Section 49(1) deals with cost calculation, the tax rate depends on whether the gain is short-term or long-term:

- Short-Term Capital Gains (STCG): Taxed as per your slab rate.

- Long-Term Capital Gains (LTCG): Generally taxed at 20% with indexation.

In case of Section 8 companies (charitable companies), profits may be exempt, but for individuals and other entities, normal capital gains rules apply.

Interim Dividend Clause – A Side Note

Interestingly, in another context under income tax law, any interim dividend shall be deemed to be the income of the previous year in which it is declared. While this is separate from Section 49(1), it reflects how the law fixes the “year of taxability” for certain incomes.

Practical Scenarios Where Section 49(1) Matters

- Inherited Property Sale – Using your parent’s purchase cost for tax calculation.

- Gifted Shares – Adopting the purchase price of the giver.

- HUF Partition Assets – Carrying forward the original purchase value.

- Corporate Restructuring – Taking the original company’s acquisition cost.

Also Read: Income Tax Digital Eye: How Your Small Transactions May Trigger a Big Tax Notice

Mistakes to Avoid While Applying Section 49(1)

-

Using Market Value Instead of Original Cost – Always trace back to the original purchase value.

- Ignoring Indexation from Previous Owner’s Year – This can unnecessarily increase tax.

- Missing Documentation – Keep original purchase deeds, gift deeds, or inheritance papers handy.

- Not Considering Cost of Improvements – These can boost your cost and reduce gains.

Conclusion

Section 49(1) of Income Tax Act plays a crucial role in ensuring fairness in capital gains taxation when assets are acquired through inheritance, gifts, or other specified modes. By allowing the Cost of Acquisition to the previous owner to be used, along with indexation benefits, it prevents over-taxation and ensures you pay only on the actual gains made during your ownership.

If you’re planning to sell such an asset, calculating your gains correctly can save you a significant amount of tax.

"Thinking of selling an inherited property or gifted asset? Let our experts at Callmyca.com handle your capital gains calculation so you don’t pay a rupee more than required!"